Prof. Anthony Bonanno, former HOD of Classics and Archaeology at the University of Malta, tells us what it's like to be an archaeologist in a country that covers 7,000 years of human history.

Chen Weizhong - viewingmalta.com

Unlike a lot of the modernised professors' offices at the University of Malta, Professor Anthony Bonanno can be found up a stint of steep stone stairs in a beautifully restored old farmhouse, amidst his books and trinkets. "Some say it's dark in here," he says when I mention how unique it is, "but I wouldn't trade it."

Born and educated in Malta, Prof. Bonanno completed his post-graduate studies in Palermo, where he got his Italian doctorate in Classics (the languages and literatures of ancient Greece and Rome: 1000BC – 500AD), majoring in archaeology. He went on to gain a PhD at the Institute of Archaeology, London University. Upon his return to Malta in 1971, he was employed as Assistant Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Malta, eventually promoted to lecturer, associate professor and professor. He became Head of the Department of Classics and Archaeology in 1989, but has, since 2012, relinquished that position.

viewingmalta.com

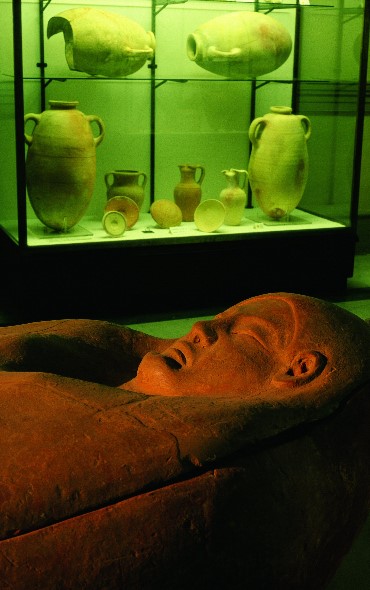

While Prof. Bonanno was away studying, he focused on ancient Roman portrait sculpture. These portraits consist of full-length statues, usually in marble, or just heads of individuals – such as rulers, members of their families, or civilians. They also occur in relief on public monuments, the subject of his PhD thesis. They're found all over the former Roman Empire, inclusive of Malta, which was under the Romans from 218 BC during the Second Punic War until 535 AD, when the Byzantine empire took over. One of the biggest break-throughs in Malta and certainly for Professor Bonanno was the finding of four portraits at the Roman Domus (town house) in Rabat, one of which was of Emperor Claudius (41-54 AD), and another of a pretty young girl, who was likely to be his daughter.

With Malta under the Roman Empire for almost 800 years, it seems obvious that there would be various surviving Roman structures all over the islands. However, apparently it isn't so. "In terms of ruins, Maltese stone was often recycled, and with all the different occupations, very few buildings were actually left intact. Most of the Roman sculptures, inscriptions, and public monuments were made out of marble, which would also be re-used in lime kilns. Even pottery - which is one of the most efficient dating instruments in archaeology - was often crushed up and used for deffun, which is a thin screed or film which was used on top of old roofs in Malta to create a cement-like impermeable surface."

The professor did go on to say that despite this practice, Malta possesses a fantastic sequence of pottery for its prehistory, which is the envy of a lot of Mediterranean countries.

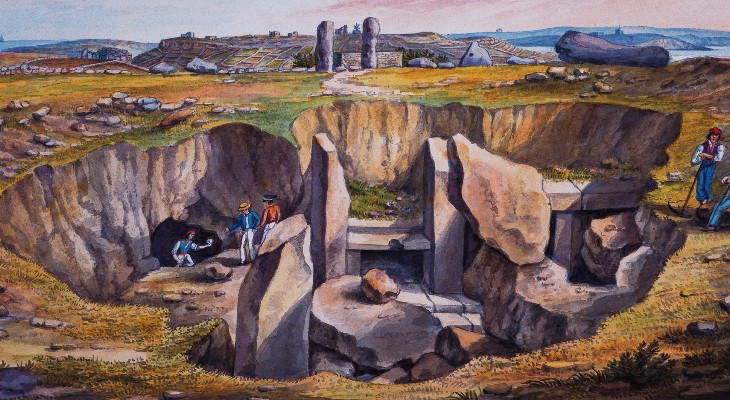

Another break-through find for the professor was during his involvement as co-director in excavations with the University of Cambridge team from 1987 to 1994, when they revealed the Gozitan Xaghra circle - a prehistoric underground collective cemetery, or hypogeum.

There were two major discoveries here; the first was approximately 200,000 human bone fragments, which was a treasure-trove of data for studies of physical shape, health and diet. The second was the impressive repertoire of art sculptures, sometimes referred to as plastic art. The hypogeum dates back to the Tarxien phase (from approximately 3,000– 2,500 BC), which is the last and culminating phase of the Temple period, during which the principal megalithic temples of Malta were built.

Xaghra circle - viewingmalta.com

For 10 years since 1996, Prof. Bonanno's department was engaged in another excavation at the multi-period site of Tas-Silg, where there are the remains of a church dating to the 5th century and strata ranging from prehistory through to the Phoenician (750 – 218 BC) and Roman (218 BC – AD 535) periods.

Prof. Bonanno's excavations are aside from his academic and teaching work. His main goal as an educator over the last 30 years has been to train Maltese archaeologists to render the country self-sufficient in this field. When he first returned to Malta in 1971, after his studies abroad, and for the next 16 years until 1987, there wasn't an archaeology department at the University. He introduced Archaeology as a fully-fledged study programme with two Maltese students in that year, at the end of tumultuous political times in the country. Now, the department is fully functioning, and provides all stages of career building in archaeology, with most of the graduates holding key positions in Malta.

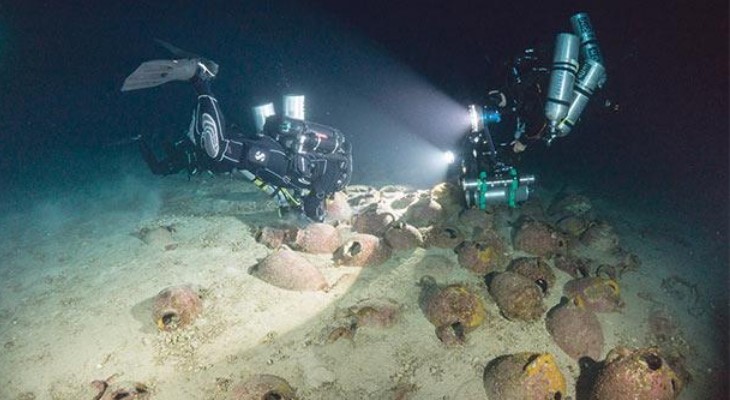

D Gration and Hyttinen/Subzone/University of Malta

The last exciting local acquisition of the department was in underwater archaeology, with the find of the oldest Phoenician shipwreck in the western Mediterranean. The wreck was found 110 metres down, and has only just recently been accessible due to a special breathing mixture devised to allow divers to reach this depth.

With Malta's 7,000-year human history, archaeology will always remain exciting on the islands, with each discovery allowing Malta, and the world, to learn a little more about foregone human behaviour, customs and rituals.