Crudely constructed out of the simplest of raw materials, traditional Maltese musical instruments are a testament to local peasant-folk’s creativity and ingenuity.

Did you know a stone could play a musical ring tone? Or that a simple reed could be transformed into a musical instrument just by drilling a hole in it? The Maltese musical tradition is built on the most basic of instruments, created purely out of anything that came to hand: animal skin, animal horn, reeds and, yes, even stones.

There was a time, in the not too distant past, when every child who played in the fields knew how to make a basic "sound producer" out of corn or wheat stems, or arundo donax reeds. This very simple reed instrument was known as a bedbut in Maltese, and was either played on its own or as part of other more complex instruments. Of course, children these days don’t play in fields anymore, and this simple skill has all but died out, along with a whole raft of traditional musical instruments.

However, one woman has made it her mission to ensure that these instruments are not completely forgotten, and is helping to keep the tradition going by researching and reconstructing them.

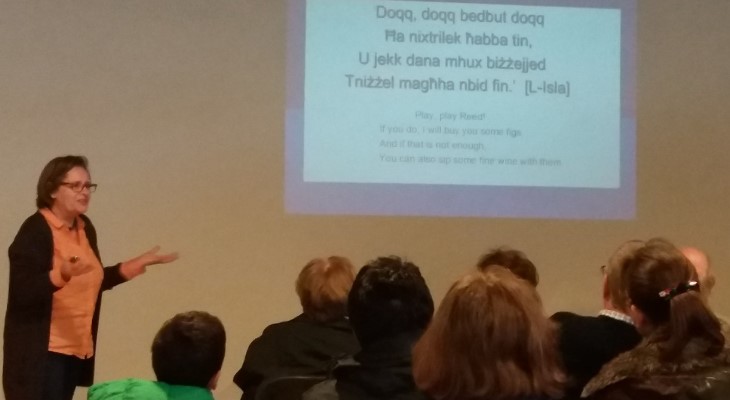

Majjistral Park - Anna Borg Cardona explains an ancient rhyme used to encourage a single reed (bedbut) to play: "Play, play Reed! If you do I will buy you some figs and if that is not enough, you can also sip some fine wine with them"

Anna Borg Cardona is a local authority on traditional Maltese musical instruments and folk music, and has written three books as well as numerous academic papers and articles about the subject. She is also responsible for compiling the Malta section of the Musical Instrument Museum in Arizona, the only museum of its kind in the world.

“The reeds are so important,” begins Anna. “This very simple reed instrument is known as a bedbut in Maltese, and it was either played on its own or as part of a more complex instrument. Everyone knew how to make one, irrespective of their social class.” The simple reed was the starting point to constructing other instruments such as the Maltese version of the bagpipe (iz-zaqq which literally translates “stomach”), an endemic form of the instrument unique to the island.

“The bagpipe was very much a peasant instrument and it was looked down upon and even ignored by the upper classes. Foreigners who visited Malta in the 19th century described how they saw only peasants playing the instrument,” explains Anna.

It has to be said that these bagpipes do look rather crude, as the entire animal, legs, tail, fur and all, except for the head, is used as the instrument. A two-piped chanter with five fingerholes on the left and one on the right is inserted into the neck end of the skin and terminates in an animal horn. They were still being made until the 1970s, and Anna learnt how to make one from “a very old man, Toni Cachia known as il-Hammarun in Naxxar” who has since passed away.

“It looks like a person is playing the whole animal, but I always think of it as giving the animal a new life,” she elaborates, adding that Toni always insisted the tail must be part of the instrument, even though it served no musical purpose. “It was so important to him to have the tail there. That’s how it always looked and that’s how it must be. The shape and method of constructing this instrument has not changed for generations,” she adds. That’s tradition for you.

Today the zaqq is difficult to make because it is not easy obtaining the material, especially as EU regulations make it impossible to get your hands on certain parts of the animal. The horn, for example, is incinerated.

The bedbut and other related instruments like animal horns and the friction drums are all quintessentially Mediterranean, but the zaqq is purely Maltese. The closest relative is the Greek tsampouna, but it does not have the animal fur on the outside. “We’ve retained the primitive look and it is very difficult to make. You have to bring everything out of the neck and leave the entire skin intact. You have to cure the skin inside and invert it again. We never developed an easier method to make this instrument,” continues Anna.

Anna Borg Cardona

Although no iconography exists before the 1700s, Anna’s research has revealed that stone bells were possibly the earliest musical instruments on the island, if they could be called as such. “In the 1600s there is a record of a big stone which was used as a bell in the valley of Mgarr ix-Xini in Gozo,” explains Anna. “Apparently this bell was heard as far away as the island of Comino. Such bells were made out of hard limestone (tal-qawwi) and would ring only if positioned in a certain way or if they had a vacuum beneath them.”

This stone “bell” was part of a strong tradition of such instruments in Gozo, a tradition which continued even into the mid-1900s. Some “village elders” Anna spoke to told her about one such bell near Ta’ Cenc. Anna set about looking for this mythical stone bell. “I found it. Actually I found four stones but only one rang. It was just a piece of rock, not carved in any traditional bell shape, but underneath it was concave. It was clearly placed there intentionally. Its position was certainly not accidental, even though it was very strangely placed,” she reveals.

Anna continued to explain how another stone “bell” was known to have been used at Dwejra to call people to Mass. This was in the days before the chapel was built, when Holy Mass used to be said at the priest’s house. Anna is not surprised that stones were used in this way. “As people handled stones to build the temples and other buildings, they would have learnt the stone’s properties very early on, and this would have been very important information for them. They knew which stone was hard, which was good for carving and which one produced a ringing sound.”

Anna also explained how these bells would have been used as a call to arms, in Maltese hagret l-armi from the Maltese word hagar, meaning stones. And it seems that these early natural instruments were more about producing noise rather than music as such. Animal horns were used to sound the alarm in the 1500s, and had a long association with carnival, which would open with the blowing of cow horns hung around the neck of male revellers.

There are certain instruments which are only associated with carnival, and the friction drum (iz-zafzafa or ir-rabbaba) was one of them. “Carnival is a time of ritual marking the coming of a new season, the start of spring. The friction drum was only used at carnival and it has sexual connotations too. In some parts of Africa it is used for initiations,” says Anna.

Xarolla Windmill Zurrieq - George Sammut sounding the bronja just as his ancestors used to do at the windmill

The conch shell, known in Malta and elsewhere in the Mediterranean as bronja, was also used at carnival and it has a long association with millers who used to sound the conch at the start of the day to announce that the wind was right for using the mill and then again to let everyone know the milled grain was ready for collection. “These were all instruments of noise rather than melody, as it was believed that noise would chase away evil and get rid of evil spirits,” points out Anna.

The guitar was one of those rare instruments to cross the social class divide. It was already present in Malta in the early 1600s, and was found in both rich households as well as in poor ones where it became synonymous with folk singing (ghana - the gh is silent). Guitars were locally designed and manufactured. Anna’s research revealed that in the early 1600s, there was an instrument maker in Valletta who was making lots of lutes and a few guitars, but by the middle to the end of that century guitars had become much more popular.

Instrument makers had at their disposal a wide range of quality materials imported from all over the world thanks to the trade networks facilitated by the Knights of the Order of St John. “Malta was importing anything and everything at the time, all kinds of exotic wood, strings and other materials even from as far afield as Brazil through trade with Spain and Portugal,” explains Anna.

Peter Bartolo Parnis - Anna (second from left) with members of the Gukulari Ensemble

The Knights brought with them not only their own musical instruments but also their musical heritage of sacred and secular music. “There was a very strong contingent of aristocracy from Italy, France, Germany, Spain and Portugal on the island who attracted a lot of craftsmen around them in the new capital Valletta,” says Anna.

These musical instruments were not just used as a statement piece but records dating back to the 1700s show that the upper classes would also learn how to play and dance too. “Teachers were coming from abroad and opening music schools, and Maltese people were going abroad and returning to Malta to open schools as early as the 1600s,” reveals Anna.

However, among the peasants, music was very much a man’s world - men constructed the instruments, men performed the music. Of all these instruments, it is primarily the guitar that has survived today as the instrument of choice with folk singing. Anna would like to see more of the traditional instruments revived, and is adamant that the art of making a simple bedbut should be taught at school.

An exhibition of traditional Maltese musical instruments is scheduled to be held in early 2019.