Reflecting the island’s long and chequered past, “Malti” is peppered with words derived from its neighbours and former colonisers, making it as colourful as its native speakers.

Bongu. Kif inti? (Good morning. How are you?) Don’t speak Maltese? If you are Italian or French or speak one of the Arabic dialects then perhaps you already do. We've discovered where the Maltese come from (hint: lots of places!) but what about their language?

Malta’s co-national language, alongside English, is the only Semitic language to be recognised as an official language of the European Union, and remains the only standardised Semitic language written in the Latin script.

That statement alone tells you that we’re dealing with a language formed by and reflecting a complex history.

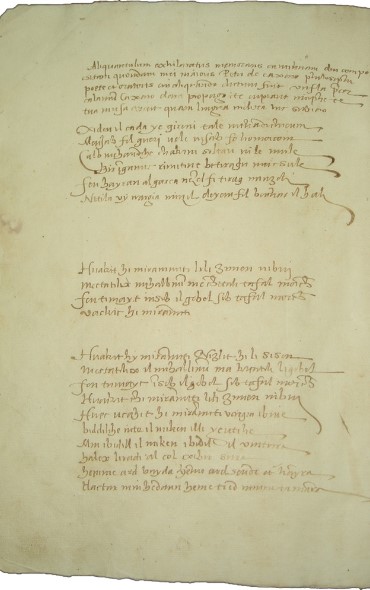

Il Cantilena by Pietru Caxaro - By Hamelin de Guettelet CC BY-SA 3.0

Maltese is derived from Siculo-Arabic, a form of Arabic which was spoken in Sicily and then introduced to Malta after 1090. Over the next eight centuries, the language evolved with a gradual process of Latinisation, with today’s Maltese vocabulary consisting of just over half the words deriving from Italian or Sicilian, around 30 per cent Siculo-Arabic, less than 10 per cent English with a smattering of French.

So settle into your pultruna, which Italians would recognise as an armchair, and let’s go on a quick vjaġġ (more Italian) through the etymology of the Maltese language. Take the word kapunata for example, that delicious dish of fried aubergine and celery, a household favourite in Malta and a staple of the Sicilian antipasti menu where it is also known as caponata, a word derived from Siculo-Arabic.

If you order snails at a Maltese restaurant, you will be served bebbux, a word which also hails from the Siculo-Arabic babbaluciu or bəbboušu, as they would say in Morocco.

And your waiter will use a trabuxu to open the wine bottle which, as you’d know if you spoke French, is a twist on tire-bouchon or corkscrew, for the rest of us.

French speakers would have recognised bongu as good morning (from bonjour) and likewise bonswa (good evening) from bon soir. Arabic speakers will immediately know that wieħed, tnejn, tlieta, erbgħa, ħamsa are the first five numbers in Maltese. And if you fly on Air Malta, you will be greeted with a warm, Arabic Merħba as the plane touches down.

There is no doubt that the source of the language we now know as Malti lies in Arabic, however, it is possible that the inhabitants of the island spoke another language until the Arab invasion in 870AD left Malta “an abandoned ruin” for 170 years.

During the first millennium, Malta was colonised by two Indo-European powers with great linguistic prestige, the Romans and then the Byzantines. Given that the Romans changed the language of the majority of their territories, it is not unreasonable to assume that Malta and Gozo may have also succumbed to this linguistic latinisation.

It is possible that the first language spoken by the Maltese was Punic, since Malta had formed part of the Carthaginian empire and changed hands a number of times during the Punic Wars until it became a Roman “civitas foederata” in 218 BC.

However, after the Arabs cleared the island and repopulated it with Sicilians hailing originally from Tunisia, Arabic may have been the adopted language. Being an island, Malta was cut off from mainstream spoken Arabic and within decades, the Arabic dialect spoken on the island started evolving and developing independently. By the time the Muslims were finally expelled from Malta in the middle of the 13th century, the Maltese inhabitants became bilingual, using their own dialect as well as the language of their Sicilian overlords.

This bilingual trend continues to this day, albeit with English, and over the centuries Malti has absorbed, borrowed, adopted and adapted countless “foreign” words, making them its very own.

The arrival of the Knights of St John from their noble houses across Europe provided a further injection of words into the local vocabulary. Their administration strengthened the use of Italian as the language of culture, as it had been in the Middle Ages when civic and notarial acts were written in a mix of base Latin-Sicilian-Italian.

Meanwhile, the Maltese vernacular continued to develop orally alongside Italian, and would only replace it as the official language of Malta, together with English, in 1934. The first written reference to the Maltese language is in a will of 1436, where it is called lingua maltensi and the oldest known document in Maltese dates back to the 15th century and is a poem known as Il Cantilena by Pietru Caxaro.

As Joseph Felice Pace writes, the Semitic element of the language must have retained its predominance in the villages where the people eked out a living from agriculture. But in Valletta and in the new harbour towns, constant contact with Sicilian and Italian mariners and traders slowly but gradually expanded the Siculo-Italian element to such an extent that over 20 per cent of the entries in a four-volume manuscript dictionary compiled in 1755 by the linguist and historian G. Agius de Soldanis are of Sicilian or Italian origin. De Soldanis also wrote the first systematic grammar of the language and proposed a standard orthography.

In the 1790s, another linguist, Mikiel Anton Vassalli took it upon himself to purify the language of Italianisms and revive it as a national language. His work would set the study of the Maltese language for the first time on solid and scientific foundations. His ultimate goal was the “civil and moral education of the Maltese people”, which he believed could only be attained through their native language. He became the first Professor of the Maltese language at the University of Malta, and saw the Maltese language as the instrument with which the Maltese nation could arrive at a “full consciousness of itself” to identify itself as a nation in its own right. A revolutionary idea at the time, and one that was met with much opposition.

Today, Maltese is taught alongside English at schools, and we are all raised bilingual, regularly switching between both languages even within the same sentence (which can be rather confusing to foreigners!) The Maltese language is having once again to adapt to contemporary life, seeking new interpretations and spellings of words created abroad which are becoming an every day part of our vernacular. The Maltese alphabet has 30 letters including two 'g's (a soft and a hard one), two 'h's (one silent!), two 'z's, as well as five short vowels, six long ones and seven diphthongs. In other words, it’s not an easy language to learn.

I should add the use of our hands as an additional alphabet in its own right, but that’s another story.

Grazzi u Saħħa!