A rare architectural and historical gem, this is the only palace of its kind open to the public anywhere in the world.

Once a common feature throughout Europe and South America, Inquisitor’s Palaces such as the one found in Birgu (Vittoriosa) represent a rare insight into the powers once held by the Catholic church.

Malta’s 500-year old palace is exceptional in many ways, not least in the fact that it has survived at all. From its original intended use as the Civil Law courts of the Order of St John, the palace evolved over the centuries to incorporate the private residence of the Inquisitor, a prison complex, later serving as a military hospital under British rule, an officers’ mess and even temporary housing for the Dominican friars after their convent and church were destroyed during World War II.

Today the Inquisitor’s Palace is the flagship of Malta’s ethnographic collection, housing a permanent exhibition on Maltese religious traditions as consolidated by the Roman Inquisition.

Watchdog against heresies

©viewingmalta.com - (Aaron Briffa)

The Roman Inquisition was established in 1542 to combat the spread of Protestantism. It was set up in Malta in 1574 when the first Inquisitor of the island, Pietro Dusina, took charge. Subsequent Inquisitors extended and remodelled the building, especially after the devastating earthquake of 1693. The last Inquisitor, Giulio Carpegna, left Malta in 1798, just a few weeks before the arrival of the French.

The Malta posting was considered a stepping stone in the ecclesiastical career ladder, with several inquisitors going on to become cardinals and two of them being elected Popes.

The Inquisition aimed to clamp down against heretical beliefs and typical crimes included blasphemy, renouncing Christianity for Islam, bigamy, solicitation during confession, magic and witchcraft, as well as the possession, reading or printing of prohibited books. Muslim slaves were often denounced to the inquisitor for witchcraft after their “magic spells” failed to have the desired effect. One fascinating Muslim “magic sheet” is on display, a wide ribbon scroll of Arabic script over a metre in length.

Sentences were often short and spiritual in nature and, contrary to popular belief, torture was rarely used and was mild compared to secular authorities. It was used to establish truth, but was never actually part of the sentence!

Look out for…

The very moment you step inside the palace, you know you’re in a special place. The palace is grand but not ostentatious or flamboyant. It was, after all, a building with a purpose, and a very sobering one at that. Nonetheless, it needed to establish and promote the authority of the inquisitor.

Look up at the ceiling in the entrance hall. Fragments of a once colourful fresco shine through, giving a hint of a quiet opulence. The majestic staircase was clearly built to impress and further boost the image of the inquisitor and the inquisition. You’ll notice a sedan chair on the landing, half way up to the piano nobile, once the mode of transport of choice for the privileged few.

The inquisitor’s private quarters on the first floor and his private chapel are lavishly decorated. The main hall features mural paintings of the coat of arms of all the inquisitors. After walking through the tribunal and past the torture chamber, head down to the prison cells, which I consider to be the most fascinating part of the palace and the real highlight!

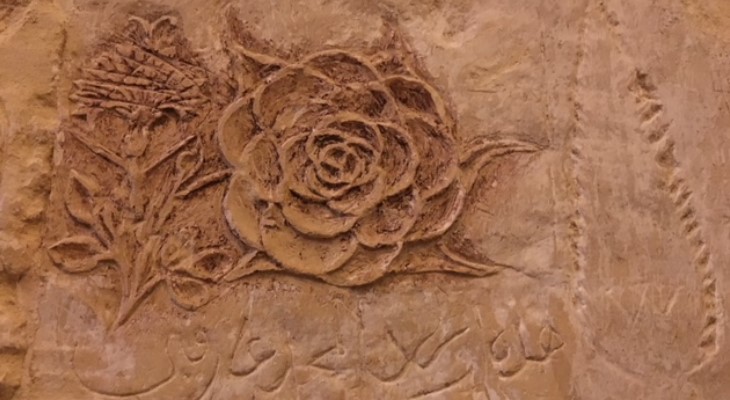

The cells are as basic and as spartan as you can imagine, with a primitive latrine system. But what makes them stand out are the graffiti etched into the walls by past prisoners. You have to know where to look and you must be patient, but do make it a point to step inside those cells and scan the walls carefully. For me, these are the real treasures here. What did these prisoners think about while they languished in those cells? It’s all there, on the walls. Yes, the walls can speak.

Adriana Bishop

I found etchings of galleys, initials, arabic script, two poignant outlines of a left hand in the same cell, the eight-pointed Maltese cross and the most exquisite flower carvings. I was also intrigued to spot primitive frescos in one cell. Were they all made by prisoners from the time of the inquisition, or did British officers add their own mementos during the early 20th century?

Don't forget to pop into the exhibitions of Easter and Christmas statuettes 'pasturi' in Maltese) which is a showcase of local craftsmanship if you happen to be visiting in Easter time.

The Inquisitor’s Palace, Main Gate Street, Birgu, is open daily from 9am to 5pm. Last admission 4:30pm. Closed on Good Friday, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day.

Open day: visit the Inquisitor's Palace for FREE on Saturday 31st March 2018